USS Oklahoma Mast

Call Sign WW2OK

USS Mast Oklahoma Today

We are extremely fortunate to display a piece of the USS Oklahoma here in Muskogee, Oklahoma at the Muskogee War Memorial Park – Home of the USS Batfish. Over 429 sailors on board the USS Oklahoma lost their life during the December 7th Pearl Harbor attack. Righted and salvaged in 1943, the USS Oklahoma was scrapped in 1946 and lost at sea in 1947 while in transit to a wrecker’s yard. Today, the anchor of the USS Oklahoma in Oklahoma City and the support mast in Muskogee, Oklahoma remind us of the cost of freedom and the sacrifice made by the brave to protect our country.

May we never forget the sacrifice of our Armed Forces members and the Attack on Pearl Harbor.

“It’s been 80 years since the attack on Pearl Harbor … Us being able to recover and identify the remains of the sailors and Marines aids in the closure for those families, but it’s also important for the Navy and the Marine Corps to honor those who really did sacrifice their lives for our country.”

~ Navy Casualty Director Robert McMahon

- 429 Casualties Oklahoma sustained

- 394 Casualties who remained unidentified after initial postwar efforts

- 361 Casualties individually identified during the project, 94% of the total

- 33 Casualties who could not be individually identified, 8% of the total

The USS Oklahoma Project

~Article from December 2022 The American Legion Magazine

A six-year effort by the Department of Defense to match disinterred remains from USS Oklahoma with DNA samples donated by families has identified the majority of crew members unaccounted for from the battleship’s destruction Dec. 7, 1941.

Following the Pearl Harbor attack, recovered remains were buried in the Halawa and Nu’uanu cemeteries. In 1947, the American Graves Registration Service (AGRS) disinterred those remains and transferred them to the Central Identification Laboratory at Schofield Barracks. Only 35 men from Oklahoma were identified at that time. The AGRS buried the unidentified remains in 46 plots at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (the Punchbowl) in Honolulu, and in 1949 a Military board classified them as non-recoverable.

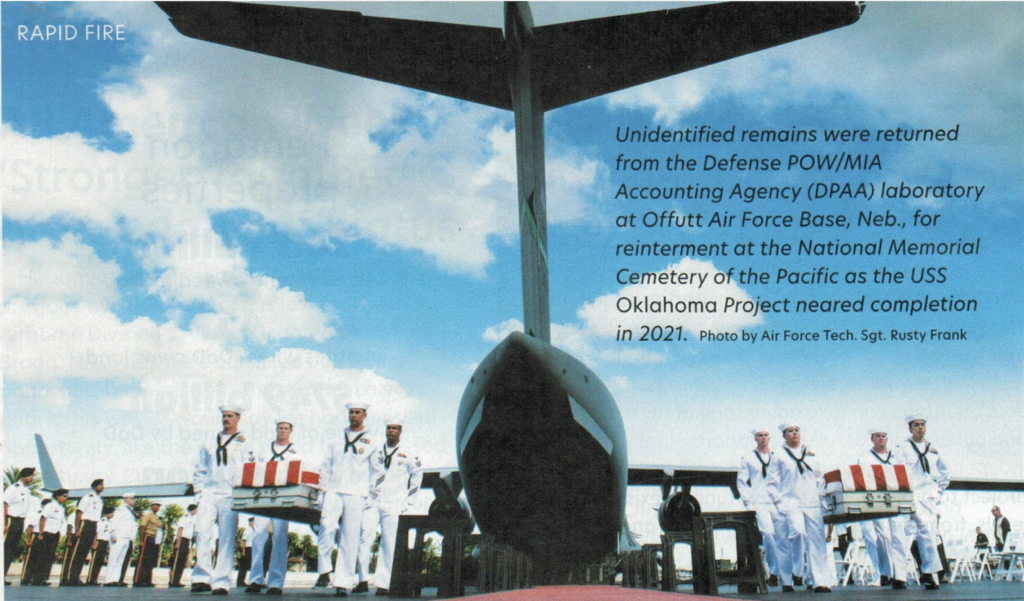

Between June and November 2015, DPAA personnel exhumed the Oklahoma unknowns for analysis. Following positive identifications, the Navy assisted families with burial and funeral coordination, travel, lodging and other expenses. The Navy also provided full funeral honors with a rifle salute, burial team and taos.

Those remains unable to be identified were reinterred in ceremonies at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. Crew members accounted for will have rosettes placed next to their names on the cemeterv’s Courts or the Missing

USS Oklahoma History

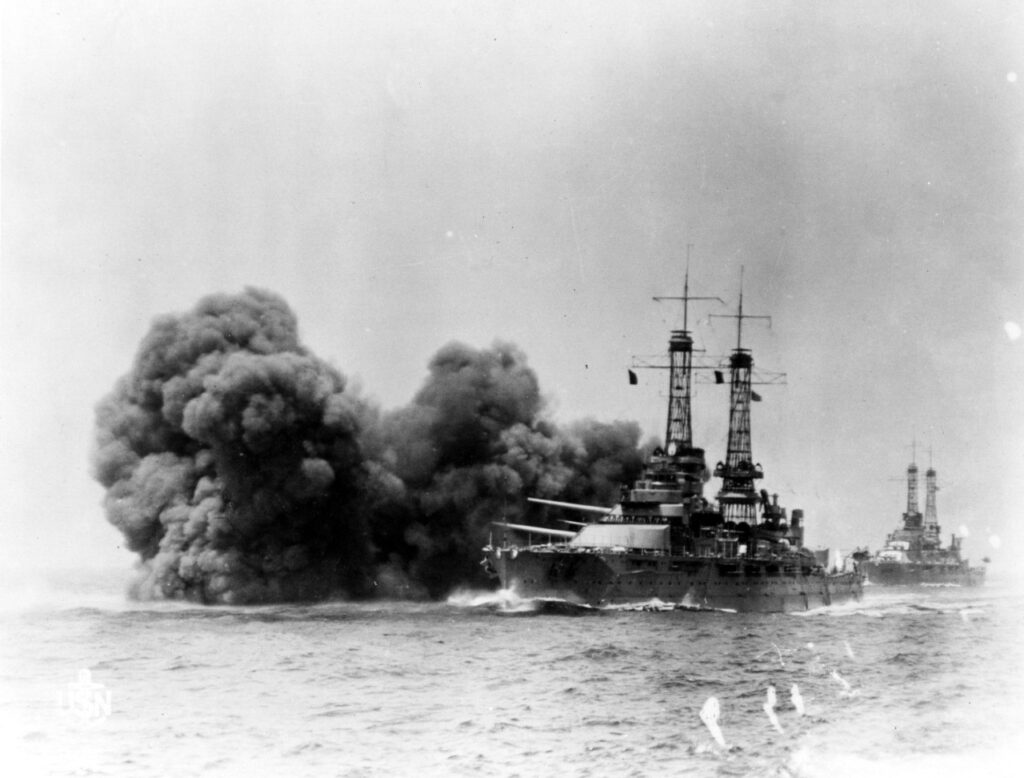

In May of 1916, the USS Oklahoma was the 37th battleship commissioned by the United States Navy. After her sea trials, she joined the Atlantic Fleet and saw duty on the Eastern Seaboard, where she protected convoys during World War I. In the years leading up to World War II, she cruised the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans as well as the Mediterranean Sea.

In October of 1936, the battleship was transferred to the Pacific Fleet. She operated for four years out of her homeport in San Pedro, California, before being moved to Pearl Harbor on December 6, 1940. Her last mooring took place on December 5, 1941, when she took her place with six other battlewagons in a location that would forever be known as “Battleship Row.”

To the crew, she was affectionately know as “The Okie.” A battleship was a small town gone to sea, her inhabitants mostly young and far from home.

USS Oklahoma survivor Stephen Bower Young, wrote: “Despite the passage of time, it seems like yesterday. My mind sees clearly the shipmates I knew so well as they emerged, laughing and talking from a hatch, portside, main deck, aft, of the Oklahoma. It is a time for morning quarters for muster, and at the urging of their petty officers, the white-uniformed sailors good-naturedly form into double ranks. They stand at ease, squaring round hats over suntanned faces. Their talk is animated and they turn in my direction. Then a cloud grows darker and I see those certain few less clearly.”

Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941

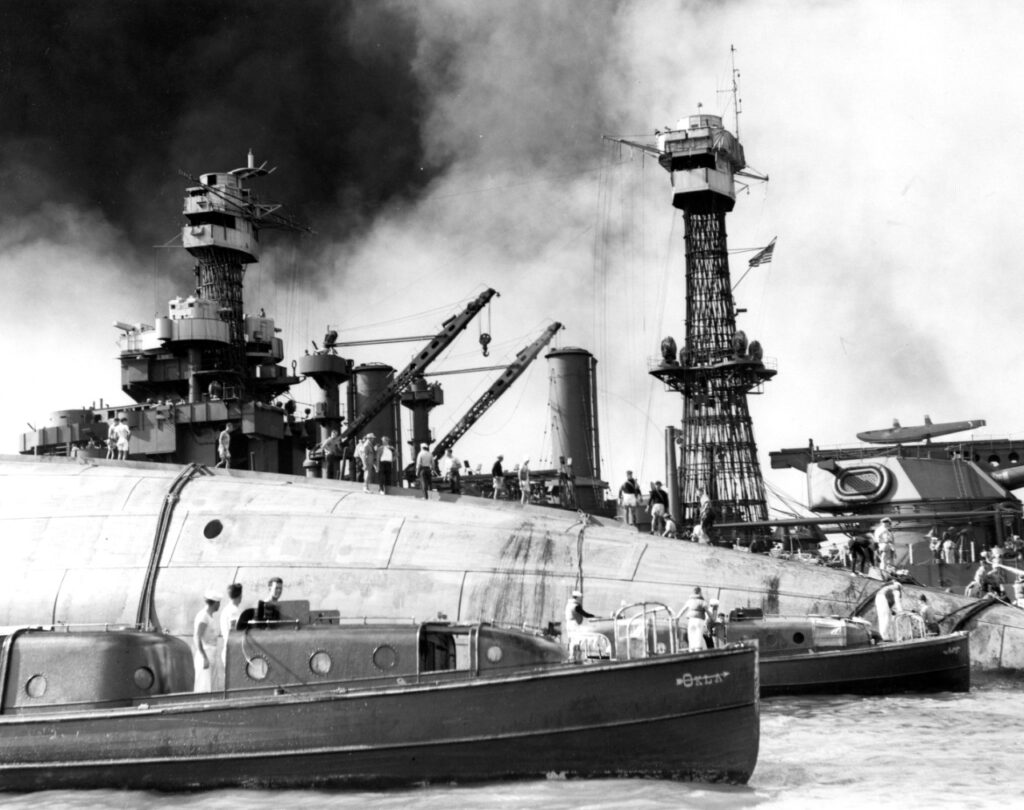

The USS Oklahoma capsized at 8:08 A.M., approximately 12 minutes after the first torpedo hit. Hundreds of men were trapped below her decks. They found themselves in a bizarre world turned upside down, in pitch-black darkness, as compartments filled with water. Death came to 429 officers, sailors and Marines, marking the second greatest loss of life at Pearl Harbor.

But not all was lost. Some men waited in compartments for rescue, while others began thinking of ways to escape their watery tomb.

Of the 14 men trapped in D-57, three made a daring escape. They swam nearly 20 feet down the trunk space, 35 feet out of the hatch and across the upside down deck, and finally ascended almost 30 feet to the water’s surface. Ordinary men with extraordinary courage swam approximately 90 feet to freedom.

The hours passed by slowly for those trapped below decks. Using hammers and wrenches, they pounded on bulkheads to draw attention to would-be rescuers. For those in compartment D-57, time was running out as the air grew foul and the water steadily rose.

Over the next two days, 32 men would be pulled from the hull of the USS Oklahoma. Eleven came from D-57, a storage compartment known as the “Lucky Bag.”

The righting and refloating of the capsized battleship Oklahoma was the largest of the Pearl Harbor salvage jobs, and the most difficult. Since returning this elderly and very badly damaged warship to active service was not seriously contemplated, the major part of the project only began in mid-1942, after more immediately important salvage jobs were completed. Its purpose was mainly to clear an important mooring berth for further use, and only secondarily to recover some of Oklahoma‘s weapons and equipment.

The first task was turning Oklahoma upright. During the latter part of 1942 and early 1943, an extensive system of righting frames (or “bents”) and cable anchors was installed on the ship’s hull, twenty-one large winches were firmly mounted on nearby Ford Island, and cables were rigged between ship and shore. Fuel oil, ammunition and some machinery were removed to lighten the ship. Divers worked in and around her to make the hull as airtight as possible. Coral fill was placed alongside her bow to ensure that the ship would roll, and not slide, when pulling began. The actual righting operation began on 8 March and continued until mid-June, with rerigging of cables taking place as necessary as the ship turned over.

To ensure that the ship remained upright, the cables were left in place during the refloating phase of the operation. Oklahoma‘s port side had been largely torn open by Japanese torpedos, and a series of patches had to be installed. This involved much work by divers and other working personnel, as did efforts to cut away wreckage, close internal and external fittings, remove stores and the bodies of those killed on 7 December 1941. The ship came afloat in early November 1943, and was drydocked in late December, after nearly two more months of work.

Once in Navy Yard hands, Oklahoma‘s most severe structural damage was repaired sufficiently to make her watertight. Guns, some machinery, and the remaining ammunition and stores were taken off. After several months in Drydock Number Two, the ship was again refloated and moored elsewhere in Pearl Harbor.

For more imagery on the salvage of USS Oklahoma, please see S-082 Captain F.H. Whitaker Collection. Then-Commander Whitaker supervised the Oklahoma salvage operations, and he donated nearly 500 images to this organization.

In 1944, the Oklahoma was salvaged and raised at Pearl Harbor. Because new battleships of greater strength and size had been added to the fleet, she was denied future service and decommissioned. She was sold to a scrapping firm in 1946, but sank in a storm while under tow from Hawaii to the west coast in May 1947.